By the time the third Test of the series began to take shape, Australia looked cornered. England held a 2-0 lead, momentum was firmly with the tourists, and Don Bradman’s captaincy was being questioned as much as his batting. History, however, was quietly preparing one of its most extraordinary reversals.

Only once has a team come back from 2-0 down to win an Ashes series. That team was Australia. And at its heart stood Bradman.

The year was 1936. England arrived in Australia on what was framed as a “tour of peace,” their first Ashes visit since the bitterness of Bodyline. Douglas Jardine had stepped away from the game, replaced as captain by the urbane and establishment-friendly Gubby Allen. Harold Larwood, the spearhead of Bodyline, stayed home, having refused to apologise, though Bill Voce did make the trip. England’s squad, rich in class and confidence, included Wally Hammond, Hedley Verity and Les Ames. Australia, by contrast, were burdened by expectation and recent scars.

England won the first two Tests convincingly. Bradman, the captain and colossus, had scores of 38, 0, 0 and 82. Critics circled. Questions were asked about his leadership and his form. What few appreciated at the time was the personal grief he carried: just weeks earlier, Bradman and his wife had lost their first child. “In the lives of young parents,” he would later write, “there can scarcely be a sadder moment.”

Neville Cardus, chronicling the tour for the Manchester Guardian, sensed something stirring. On the eve of the third Test in Melbourne, he reportedly warned Allen: “For heaven’s sake clinch the rubber at once. Bradman cannot go on like this much longer.” It proved a prophetic misreading.

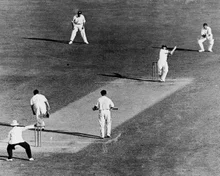

The Melbourne Test unfolded under conditions that demanded tactical clarity as much as technical skill. Rain transformed the pitch into a treacherous sticky dog. Bradman declared Australia’s first innings at 200 for 9, sensing opportunity. England collapsed into chaos, wickets tumbling rapidly. Then came a moment that defined the series. Bradman, desperate to avoid batting again that day, spread his field and instructed his bowlers to bowl wide, inviting England to survive. Allen refused to take the hint. He pressed on, inching England to 76 for 9, eating up overs but handing Bradman the initiative.

What followed was a masterclass in gamesmanship. Bradman delayed England’s declaration by feigning confusion, sent his tail-enders out to shield his top order, and ensured Australia faced just 18 balls before bad light ended play. In three hours, 13 wickets had fallen. The balance of the series had shifted.

When play resumed, more than 87,000 packed into the MCG. Bradman walked in with Australia 221 ahead. Seven hours and 38 minutes later, he walked out having scored 270. Alongside Jack Fingleton, he added a world-record 346 for the sixth wicket. England were set 689 to win. They never threatened.

Allen, outmanoeuvred and deflated, unravelled. In letters home, he lashed out at his own side, dismissing them as “rotten” and revealing a captain beaten not just by skill, but by will.

Bradman was not done. He followed his Melbourne epic with 212 at Adelaide, leveling the series, and then a commanding 169 in the final Test as Australia completed a stunning comeback to win 3-2. From despair to dominance, the transformation was complete.

In 2001, Wisden named Bradman’s 270 the greatest Test innings of all time. It was more than a mountain of runs. It was strategy, resilience, and character fused into one performance.

Cardus, by then utterly captivated by Australia, captured the essence of England’s undoing: it was, he wrote, “a failure as much of character as of technique.” And at the centre of it all stood Bradman, scripting the most enduring chapter of Ashes history.